River Edge Ecological Restoration

Bijbehara, Jammu and Kashmir

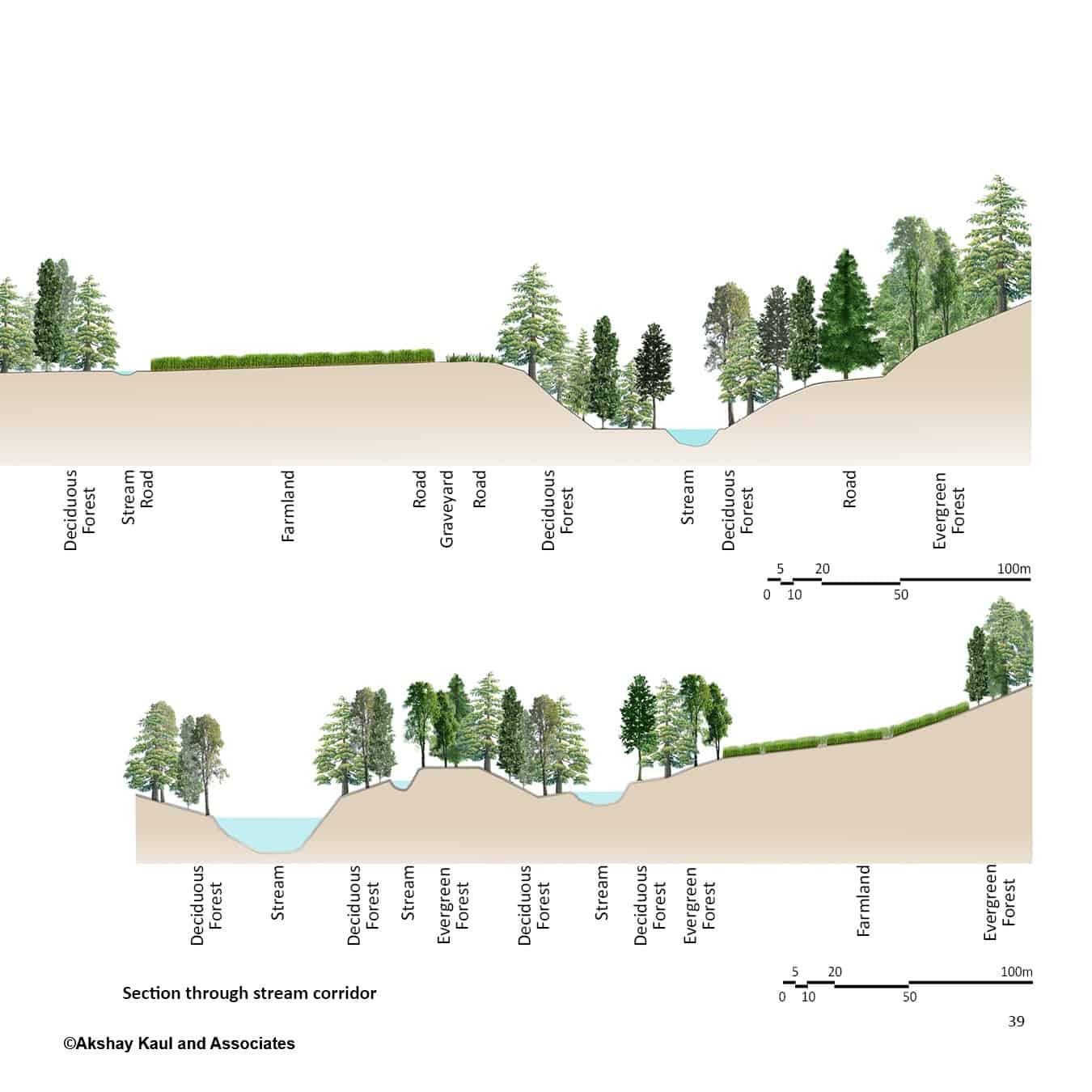

Bio engineering is the mixture of principles of biology and tools of engineering. Bio engineering is cost effective use of vegetation required for slope stabilization and control run off and their effects on erosion of soil and transportation. It is locally adapted method to control landslides and loosening of soil. Bio engineering plays a key role where civil engineering fails and answers to common slope stability problems to road construction and negative impact of road construction. Proper roadside drainage need to be provided to divert heavy run-off are some of the examples required in bio engineering for safer place.

In general, bio engineering is the attempt to regulate and modify bio-system so as to control natural biological systems. These are extensively used for stream corridor stabilization and erosion control, slope stabilization of hills and along roads and highways especially along hillsides.

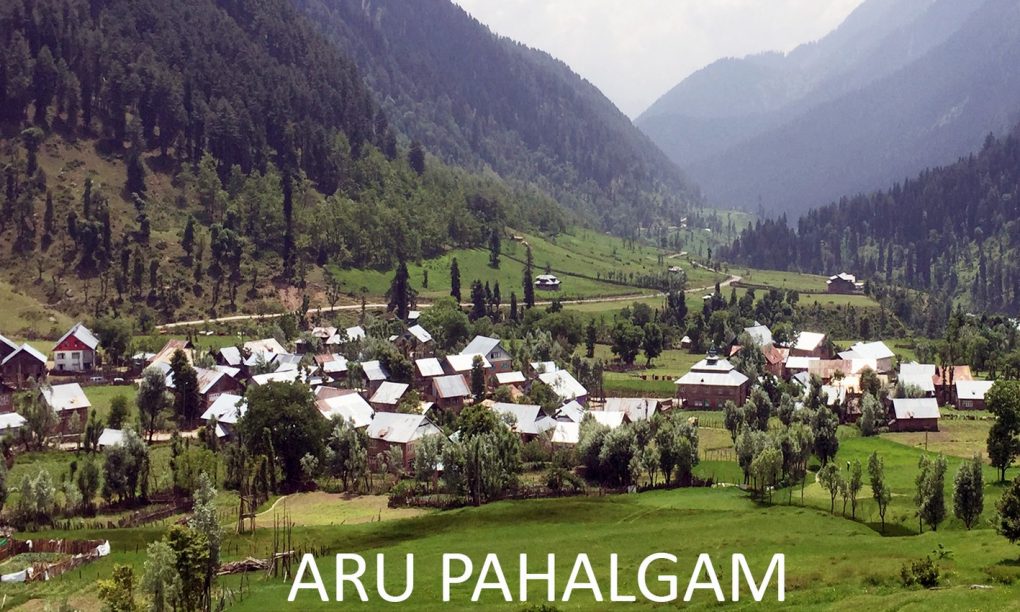

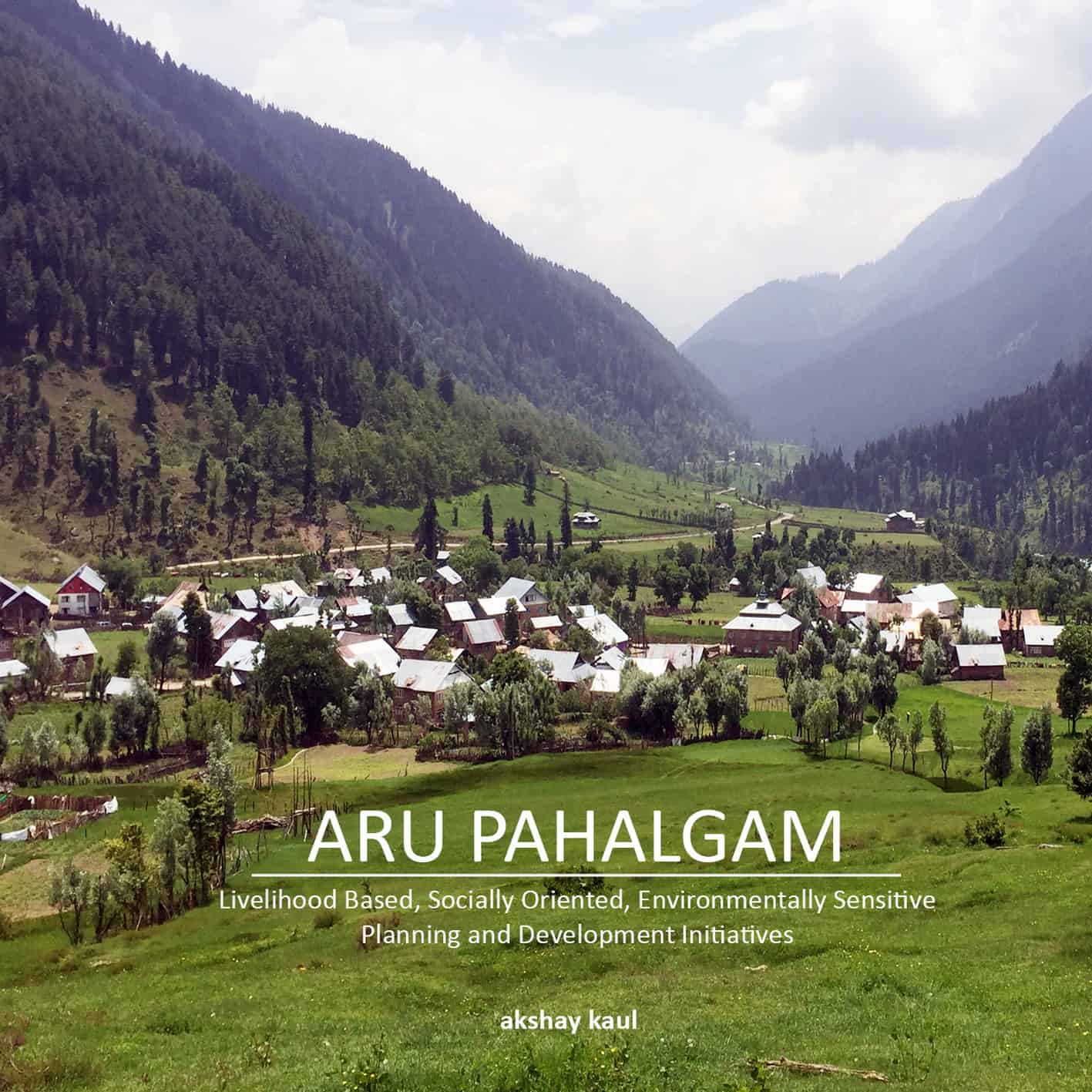

Aru Village

Pahalgam, Jammu and Kashmir

Aru valley is at an altitude of 2400 metres above mean sea level, little higher than Shimla. It is part of the larger Lidder valley (also spelt as Liddar). The Lidder valley gradually rises in elevation from south from 1600 metres to 5200 metres in the north.

The Lidder basin is surrounded on the south and southeast by the Pir Panjal Range, on the north by the Sind Valley and on the northeast by the Zaskar Range. The Liddar valley is surrounded on three sides by high mountains, the Saribal – Katsal ridge (4800 metres) on the east, the Wokhbal (4200 metres) on the west and Basmai Kazimpathlin. It is about 50 km long and has a maximum width of 5 km. The Lidder drainage basin has an area of 1134 km2 and its discharge is about 10% of the total volume in river Jhelum.

The Lidder valley begins from the base of the two-main glaciers, the Kolahoi and the Shishram which are now shrinking at a rapid pace. This is the origin of two main streams, the West and the East Lidder which merges into one before Pahalgam. After passing through Pahalgam, the Lidder passes through a narrow valley and ultimately fans out on to the wide alluvial fan near Aishmaqam. The Lidder meanders and forms a braided stream in the southern plains of the valley.

Aru valley has a Sub-Humid Temperate with nearly 80 per cent of its annual rainfall concentrated in winter and spring months. Aru receives about 1200mm of precipitation spread over the year and almost evenly distributed except in the months of September, October and November where it is minimum. The temperatures in winter drop down to -13 degree and 25 degree in summer.

The vegetation of the region displays characteristic mixture of temperate flora with This zone extends up to the altitude of 2200 metres with Pinus species, and Cedrus deodara grow along with broad-leaved species like Acer caesium, Juglans regia, Salix species, Populus sp and Robina pseudoacacia. Indigofera heterantha, Randia tetrasperma, Viburnum grandiflorum, Berberis lyceum, Parratiopsis jacquemontiana, Daphne mucronate, Verbascum Thapsus, Ajuga bracteosa, iola odorata, Hypericum perforatum, Verbascum thapsus are found as shrubs in open landscape in the region. The evergreens may either appear as pure colonies or mixed species. In Aru, predominantly these appear as broad leaf along the eat and west river and Salix along smaller streams.

Any Geological setting has three components primarily the lithology, stratigraphy and structure. Essentially, the geomorphology of any area is created by the interplay of these three components. While structure also reflects tectonics, lithology and stratigraphy are obviously intimately related to each other. Aru much like Pahalgam is a V shaped valley at the base of a U shaped valley. The lithological formations of the study regionrange from Carboniferous to Triassic with recent formations near the rivers and the glaciers of the Liddar valley. Much of the spectacular character of the present topography of the northern part of the Lidder Valley has resulted from the glaciations in the remote past. Glaciers carry many types of fragments and particles embedded in them. Those particles placed along the base of a glacier may scratch, grind or groove the rock surface during the movement of ice. Such fine cut lines and scratches become exposed when the glacier disappears. During the advance movement of glacier ‘straited erratic’ may be seen in Aru as evidences for the glacial movement.

Fluvial geomorphological landforms are produced by fluvial process. The long stretch of the West Lidder from the source at Kolahoi Glacier to its merger with the East Lidder at Nunwun is constituted a fluvio-glacial landscape. The fluvial landforms present in the study area are mainly gorges and terraces. The gorge at Kalwan known as Kalwan gorge carved through the thick formations of volcanics, limestones and calcareous sandstones is about 3-4 Km long, 100- 150mts deepp. This gorge is the fluvial erosion feature. Another fluvial feature is the terrace. The study area is mostly characterized by the depositional terraces. The terraces are found between Mundlun and Aru along the West Lidder and are also found at Nunwun. The terraces found in the study area and in the surroundings are mostly un- paired (Kaul. M. N., 1994). In addition to above morphological landforms present in the study area there are also presence of mass-wasting (land sliding) between Nunwun to Aru along Pahalgam-Aru road. The sliding material commonly found is the mixture of boulders, gravels, clay and silt overlying on the inclined limestone beds.

The V shaped Aru valley is bound on the both sides from the streams of glaciers melt that come down from Kolahoi glaciers in the North as the West Lidder river.

Ecology Restoration, Water, Landscape & Environment Planning

Tassavur - 2017

Ecology Restoration, Water, Landscape & Environment Planning…

2 Day Workshop on Tourism, Nature, Culture, Architecture Urban Development and Arts

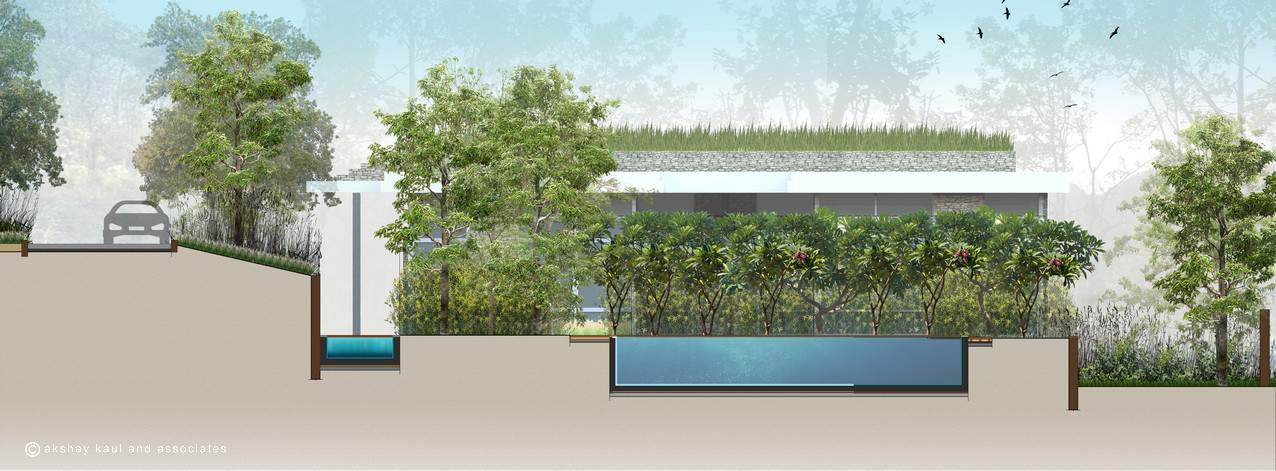

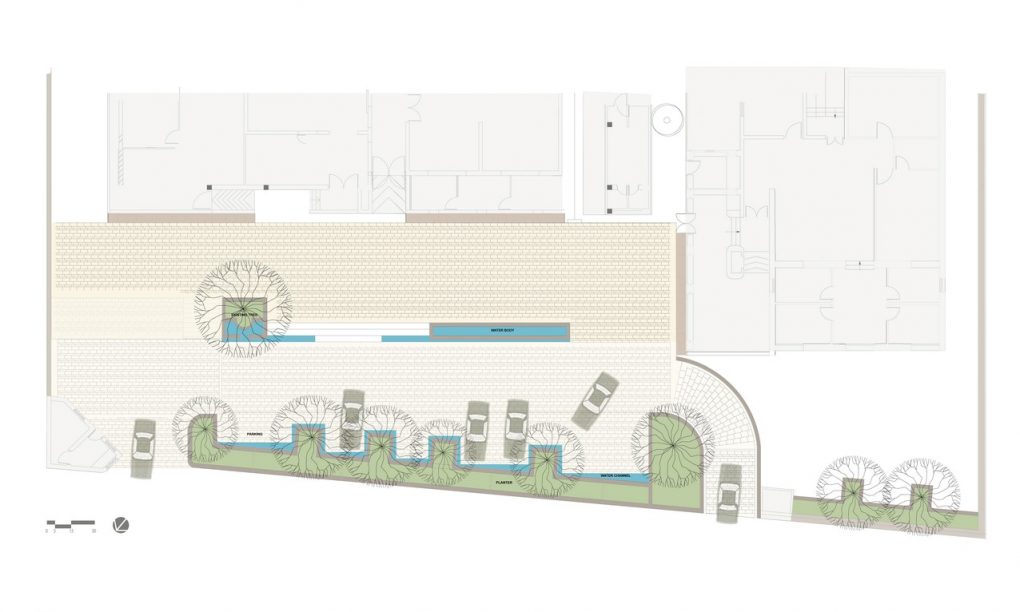

Satya Sadan

Jindal House

Roshanara’s Net by Mary Miss

Akshay Kaul

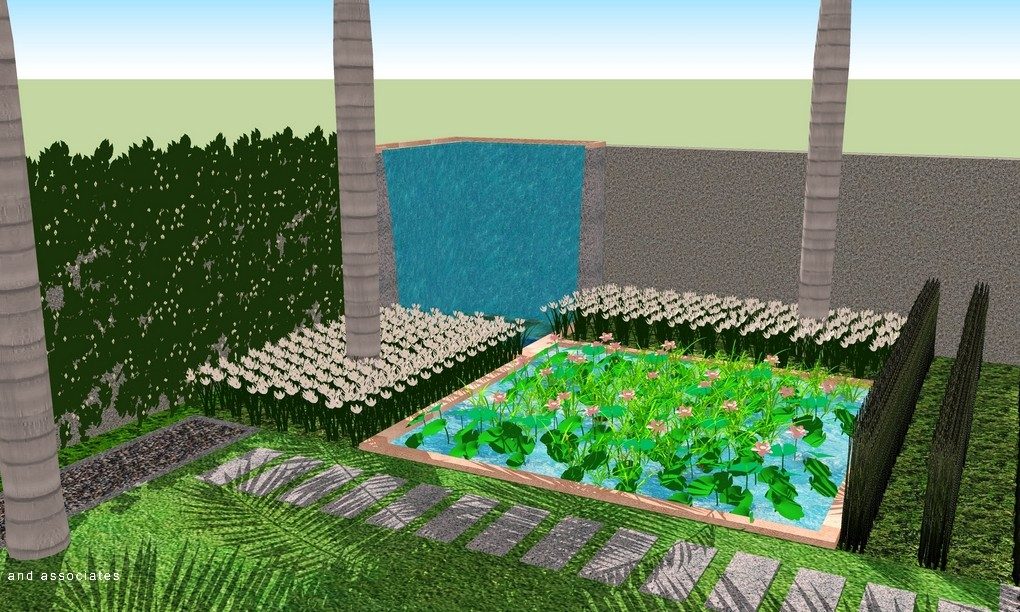

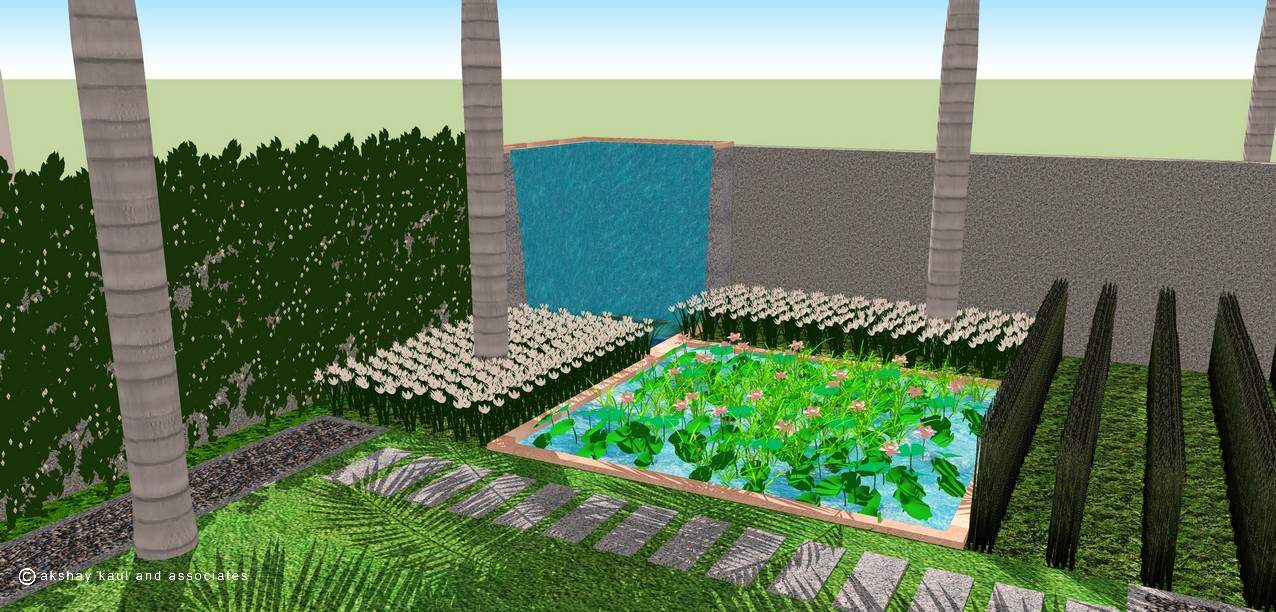

A temporary garden of medicinal plants–ayurvedic herbs, trees and bushes–was the focus of this project in New Delhi, India. The abstracted gardens found in the patterns of textiles and rugs were the visual basis for this temporary multi-part installation. 100 diamond-shaped units made up of evenly spaced orange pipes covered the grounds of a seventeenth-century Mughal pavilion in a city park in Delhi. At the center of each unit was a tin sheet outlined in blue pipes containing the name of one of the medicinal plants with text in Hindi and English describing its use. Looking out over the earthen surface of the park paved with orange and blue linear elements, the image of threads accumulating to create a pattern was evoked.

As the city of New Delhi modernizes and implements policy decisions to create cleaner air, for instance, neighborhoods like those adjacent to this park have suffered as textile plants, markets and other industries have closed. Looking at issues of sustainability, it becomes apparent that it is important to consider issues ranging from the micro to the macro scale. This project focused on the small scale—the health and well being of the individuals and their communities.

After initial visits to Roshanara and its neighborhoods a number of questions came to mind: Could this rather neglected archaeological site become more of an amenity to the community (and by implication, could the many heritage sites found scattered throughout the city become assets to their immediate neighbors)? Could the place be used by a more diverse group of people including women and children? By radically transforming the site for a short period of time, giving it a new use and meaning, is it possible to choreograph a different pattern of urban space, to create a map of that area other than the one that is currently understood?

The idea of the garden was taken beyond the boundaries of the immediate site. A quarter-mile of fence along the park’s eastern perimeter was wrapped with a band of orange cloth naming the medicinal trees in English and Hindi to be found in the park. Inside the park itself those trees were banded and named with the same material. Three “Portable Parks” —wheeled carts carrying medicinal plants—were transported around the neighborhood to announce the times and dates when Ayurvedic specialists would be speaking at the garden, where 2000 plants lined the base of the pavilion.

A new set of connections have been made between Roshanara’s tomb and the neighborhood. A temporary net has been cast between the two.